“So… otherwise, how’re you doing?” This question, phrased by Grammy award winner Patton Oswalt in a recent NPR piece, reflects a collective weariness. As Oswalt continued, “There is just this overall gloom – political, psychological, emotional,” referencing the negativity of today’s social fabric and public institutions.

“So… otherwise, how’re you doing?” This question, phrased by Grammy award winner Patton Oswalt in a recent NPR piece, reflects a collective weariness. As Oswalt continued, “There is just this overall gloom – political, psychological, emotional,” referencing the negativity of today’s social fabric and public institutions.

It’s no surprise. Popular culture in recent years has fostered, rather than moderated, human qualities of greed, disingenuousness, xenophobia, and impatience.

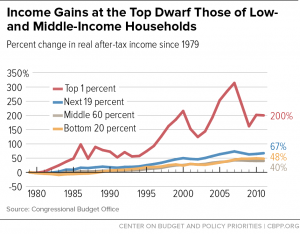

We survived the economic meltdown of 2008, and have since gone on to post record stock market highs. But the CEOs hawking the subprime loans that led to the crisis escaped prosecution and profited handsomely while being bailed out by the public. And while the average Joe ended up no better off, and the economic disparity between the super wealthy and the workers skyrocketed, the popular narrative that emerged blamed government, not corporate greed, as the culprit.

In “Six Signs that our Culture is Sick with Greed,” RJ Eskow observes that “Today’s national culture of greed is also an expression of pain and fear.” Problems of poverty and economic instability are prevalent, but worse, we misunderstand the reasons for these problems. We too easily accept that immigrants, environmental regulations, or urban elites are to blame for job insecurity and low wages.

These messages of misplaced blame serve to exonerate people at the top of the economic ladder – the one percent who have prospered while poverty has increased.

Building a strong and broad base of support is necessary for the emergence of what I might call a “Positive America” coalition. This notion comes from the essay mentioned in my last post about how Norway built their social democracy while Germany was becoming a Nazi state. But given the extreme polarization of the electorate, building such coalition isn’t simple. It certainly won’t happen while progressives blast Trump voters as deplorables or racists, or while conservatives frame progressives as out-of-touch urban elitists. We need to find common ground.

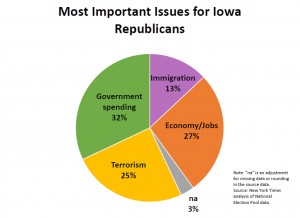

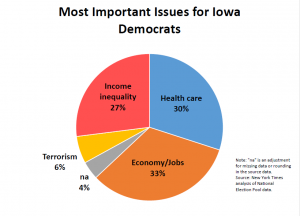

Here are two pie charts from the New York Times dating to February 2016, when presidential campaigns were at full throttle and a dozen candidates were still in the race. The fact that Democrats and Republicans have such divergent values is apparent from a quick look at these graphs.

However, something more important stands out here: Roughly a third of respondents from both parties see jobs and the economy as their most salient issue. This is where coalitions can grow, in the ground where concerns are shared. This fact also shows why identity politics can’t bridge the political divide.

Given common concerns about jobs and the econonmy, it is worth pondering what a bipartisan, pro-jobs, secure economy platform might look like. Crafted carefully, it could bridge at least part of the gap between left and right. And perhaps local control – a rare rallying cry in that it is not exclusive to either progressives or conservatives – might be a way to approach people about building a strong economy.

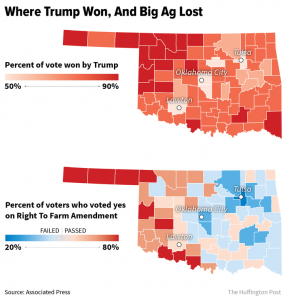

The story of Joe Maxwell helps illuminate how to reestablish common ground. Joe Maxwell led a recent ballot measure campaign in Oklahoma. Living in a solid red state, Joe doesn’t buy Democrats’ post-election analysis that their party’s future lies only in urban and suburban districts. And Joe has reason to challenge that view: He spent November 9th 2016 celebrating victory in an election everyone expected him to lose.

The Oklahoma voters in this race rejected a so-called “Right to Farm” statewide initiative. This measure was designed to insulate factory farming from state level environmental, food safety and humanitarian regulations. When Joe signed up to fight the heavily-funded industrial agriculturalists behind “Right to Farm,” polling showed those on his side at just 15% – while 64% supported the measure.

The Oklahoma voters in this race rejected a so-called “Right to Farm” statewide initiative. This measure was designed to insulate factory farming from state level environmental, food safety and humanitarian regulations. When Joe signed up to fight the heavily-funded industrial agriculturalists behind “Right to Farm,” polling showed those on his side at just 15% – while 64% supported the measure.

Predictably, the other side tried to characterize Joe as an extremist. (Polarization usually works!) They pointed to the fact that Joe worked for the Humane Society. ““HSUS is a vegan organization — they don’t want people to ultimately eat meat,” Will Coggin, research director for the Center for Consumer Freedom, claimed. But despite Joe Maxwell’s affiliation with the Humane Society, he also runs his family’s hog farm. The insults didn’t stick.

What made Joe’s campaign a success was that he took time to actually connect with people one-on-one. “You have to go meet them,” Maxwell says about voters. “You have to go be where they are. It’s about who they are, and showing them that you are like them, that you share their values.”

Joe developed a coalition, starting with family farmers who, like Joe, feel a human connection to their animals. He also drew in environmentalists, animal rights activists, and food safety advocates.

This strategy led Joe Maxwell’s underdog campaign to victory, in a state heavily carried by Donald Trump. In fact, they won by 20 percentage points! And in so doing, Joe offered a model for progressives elsewhere: Go meet those who might be your adversaries, and let them know that you share their values.

This strategy led Joe Maxwell’s underdog campaign to victory, in a state heavily carried by Donald Trump. In fact, they won by 20 percentage points! And in so doing, Joe offered a model for progressives elsewhere: Go meet those who might be your adversaries, and let them know that you share their values.

Such coalition-building can help us move past polarization. Joe’s story shows that we can create dialog, re-establish a “Positive America,” and build common ground – once we stop fixating on the celebrity in the White House.

A well written and educational piece. I didn’t know that about Joe Maxwell. This was enjoyable to read and it flowed easily.

A focus on commonly held goals makes sense and identity politics isn’t the bridge of the political divide. I believe that one of the reasons that gay marriage became accepted as relatively widely and quickly as it did over the last decade is because more and more brothers, sisters, cousins, friends and others that are known, loved and respected took the risk of saying, “I’m gay.” At this point, I don’t see transgender/genderqueer people as having as much support. Despite the pie chart above, I believe that shrinking the socioeconomic divide is a potential common goal.