The Otrohy Resort is about as unassuming as a commercial lodging establishment can be.

7 June 2025

On Saturday morning we left Kyiv, traveling a couple hours north into the country. It was notable to me that we passed only one apparent military facility; Katya explained to me that the Ukrainian military has very carefully decentralized its operations so as to make any one location a low-stakes target. This is how people in this country have to think: What is, and what is not, a viable target of Putin?

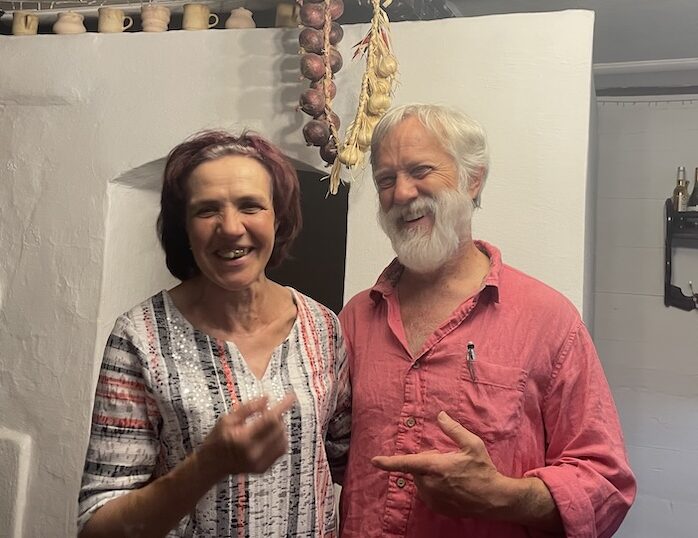

Turning off the highway, a dozen or so kilometers brought us to a tiny inn – on an upaved road and with no visible sign – called Otrohy Resort. I only discovered the sign on our second day since it sits inside the front door! The place is ancient and has been run by the same family for many years. We were served lunch, which included a hearty bread, salad, and hummus. The proprietor, Val, insisted on toasting us with some of his homemade grapa (grape vodka) which was surprisingly smooth. We also met Angel, his wife, and their kitchen helper Valentina, who has such a lovely smile that I asked to get a photo with her.

After lunch, we settled into our cabins. Vytas and Katya napped, while I went for a walk in the nearby pine forest. It’s was quite pleasant, though clearly more plantation than natural forest. I found a logging landing were a few hundred 4-meter pine logs were cut and stacked. A much smaller number of birch were also piled nearby, and a few oaks. Apparently the monoculture isn’t seamless. But at the same time it seemed to represent decent silviculture, since the logging was selective and there weren’t any slope, wetland, or other ecological concerns.

Valentin, the co-owner and host at the Otrohy Resort, served us homemade grapa as a greeting toast.

Dinner was a lovely Georgian flatbread with cheese, along with a turkey casserole of some kind and salad along with more of their rustic wholegrain bread. Very tasty. Most of the food we were served, I learned, was either grown on the property or supplied by local artisans. Over dinner we enjoyed some in-depth discussion; I suspect that this is the norm for Katya and Vytas. Our topic was the integral community’s difficulty accessing a reasonable perspective on Ukraine. Many folks take a simplistic attitude toward the Russian attack on Ukraine, suggesting that maybe some form of advanced diplomacy would be more effective than a robust military defense. This, understandably, I think, is a recurrent topic for this family.

We also discussed the story of Angela, our chef, and her mother, who are from Mariupol. Angela hasn’t been back in years, but her mother Ludmila, who stayed, had to get out once the Russian occupation began. This was of course not permitted. So, despite being near 90 years of age, she had to make a wildly roundabout trip to avoid Russian prohibitions and surveillance – first into Russia, then to Georgia, then on through Turkey, Greece, and Poland before re-entering Ukrainian territory. Ludmila is a sweet older lady with a bit of fire in her. Rural village life is not what she would have chosen, but she had to get out of Mariupol. (A photo of Ludmila and Daniel appears in the first post of this series.)

Kateryna and Vitas are my very generous friends who hosted my trip to Ukraine. This is their “K & V weekend!”

Katya and Vitas headed off to take a dip in the pond. I stayed behind, reminding them that this was originally earmarked as a “K & V weekend.” Once alone, I borrowed Angela’s guitar and played some tunes. I began outside, but the no-see-ums were numerous and invasive, so I went in. It was wonderful to just sit and play; it’s been a long time since I had an open evening for music. I ran through a half dozen or more songs before Katya, and later Vytas, returned, at which point we sang several songs together. It was a nice way to enrich our connection, as well as a chance to revisit my musicality.

The night was incredibly quiet, stillness laced only by frogs and birds. I could easily have fallen directly asleep. But knowing my tendency to awaken in the night with my head full of thoughts, I opted to put some of those ideas into my journal first.

8 June 2025

Writing was the right move. I slept soundly for seven hours, which left me feeling well restored and refreshed. Adding to my wellbeing and contentment, I was able to lounge amid the blissful calm of nature in the morning – meditating on the porch, taking a dip in the pond, exercising on the dock. All in immediate, blessed contact with nature. This is perhaps the experience I miss the most while traveling in urban environments.

As breakfast approached, I headed back to the lodge to again pick up Angela’s guitar and sit on the patio cranking out tunes in the morning sun. Most of the songs I know are melancholy or wistful. But then Ludmila, Angela’s mother from Mariupol, came out and with her two-toothed grin, insisted that I play something she could dance to. Keep in mind that we do not share any language! But she was animated enough that what she wanted was unmistakable. So I picked up the pace and started in with the rather randy song “Griselda.” It was just what Ludmila wanted! She immediately began dancing, and to my delight Katya came around the corner and videoed the scene. This was one of my most cherished moments in Ukraine: Two humans, with minimal cultural or language connection, joyously joined in creative expression!

Valentina, who works at the Otrohy Resort, and is also the village librarian, has the most beautiful smile!

At breakfast Katya proposed that we attend a choir performance in a nearby village. As we got ready we found that Ludmila wanted to join us. The three of us headed on a short drive to the performance. On this ride, I learned that Ludmila is in fact a retired electrical engineer who spent forty-two years working in industry: Another revelatory treat! I had not thought of this charming babusha in light of a career, but rather as “just” a grandma. We all, it would seem, contain multitudes… and we so easily overlook the richness others hold just beneath the surface.

My guess is that there are displays like this of fallen heroes in nearly every village in Ukraine. It confirms the sense that everyone is part of the war effort.

The performance was one of those small-town events magnified in performativity and pomp by being a rare chance for people to dress up and gather. It was held at the village cultural center, which barely even had a sign (a placard in a window was pointed out when I commented on the lack of designation) but hummed with geriatric village energy. I was shown the library by a proud Valentina, the librarian and resort cook whose smile I so adored. I was shown an honor display of locals who had fallen victim to this war. And I was toured through the “museum,” essentially, boxes and heaps of stuff in the back of the auditorium. As we took seats I witnessed babusha after babusha, hunched, huge, and headscarfed, greet each other like long lost sisters.

The matriarch’s choir was the featured performance at the village cultural event.

The event started. A regional official spoke briefly, sharing predictable niceties and gratitudes, followed by the village leader. And then the choir came out: Seven women, aged from perhaps 50 to 80, in matching traditional dresses, belted out their tunes with an energy that made their microphones seem superfluous. I cannot say that they were often in consensus on pitch. But their stoic enthusiasm more than made up for any gaps in their vocal acumen. Many pieces were accompanied by accordion, and the set list included an acrobatic dance by a charming 10-year old named Milana and some poems by the octogenarian poet-laureate-of-the-village.

This clearly pre-Christian offering was inobvious, but the locals mafe sure that I saw and appreciated it — thus making clear its symbolic value to them. Here Valentina and Ludmila pose with me.

It was quite the scene: 30-40 folks in an auditorium that could have fit 150, roughly 85% female and with an average age well older than me. Such is Ukrainian village life in the 21st Century. Clearly this was the event of the month, if not the year, in the village.

I was expecting to be charged a ticket fee of some kind. Instead I was directed to a simple shoebox with a slot in its lid: All proceeds, however humble, are donated to the war effort. Between this and the honor display of war heroes, it was patently clear that, though nobody seemed to dwell upon the war, it was woven into the life of even tiny villages.

Our beautiful hosts, Val and Angel, wouldn’t let us leave without a gift of a bottle of local wine.

Upon leaving we were called to a corner of the cultural center’s yard to have our pictures taken with an effigy of sorts. The best explanation I got was that this figure represented fertility and the coming of summer; blessing her meant assuring a good harvest. What a delight to have the Divine Feminine brought to my attention in this largely Orthodox culture! I learned later that the villagers were honored, even awed to have an American “journalist” (not sure where that came from) attend their small village celebration. This is not a community often visited by foreigners. Perhaps more significantly, I noted that my foreignness was held as more a blessing than a curse.

We ate a very nice lunch, again prepared by Angel, for our final meal at the resort. It was difficult to say goodbye after only 24 hours in the company of this family. Indeed I felt that I’d been treated royally – and that I’d been blessed to experience a bit of authentic rural Ukraine few travelers witness. There was a strong undercurrent of heritage in my observations of the place and its people. More than anything, it was the simple human warmth, sharing, and smiles that transcended our cultural differences and made my heart break a little upon parting. Valentin gave us each a bottle of local wine as a parting gift, making me wish I had a gift to give in return.

From Otrohy we drove 90 minutes to another village, this one called Vovchok. In English this word translates into wolf-pup, which hints at an origin story that I didn’t get to hear. Again, the town had no apparent signage or commerce. We pulled into the deserted main square to search out the Vovchok Folk High School we had come to visit. Before finding it, we discovered a cross at the center of the square honoring victims of a famine known as Holodomor, engineered by Stalin in 1932-1933, that killed 5-7 million Ukrainians. The famine was real, but was selectively used to punish Ukraine (despite it being a key grain producer for the Soviet Republic) for anti-Soviet leanings. It is clear that antipathy toward Russia is widespread here, even in quiet village squares, nearly 100 years after Holodomor.

We looked around for the school. There were several buildings fronting the deserted town center that could have been a school, but again, no markings or signage were visible. As we wandered, a single pedestrian appeared who was able to point us to the correct building.

The unassuming, but beloved, school building in Vovchuk that is being converted to a Folk High School by Serhii Cumachenko and his allies.

There we met Serhii Chumachenko, the charismatic founder of Ukraine’s first Folk High School. This is a new part of a larger Folk High School movement I first learned about from podcasts involving Lena Anderssen, Zak Stein, and Tomas Bjorkmann. Folk High Schools are part of the Bildung movement, and despite their name are focused more on adult education than teaching teenagers. The core tenets of this movement include civic education combined with individual self development. If I understand history correctly, this movement is a key reason Scandinavia has the most effective social democracies and humanistic societies in the world. In any case, there were a few other people around, the only one of which I recognized was Jaroslav, a graphic, event, and social systems designer I’d met at the theatre on Friday.

I experienced an immediate kinship with Serhii. He was wearing a mountain rescue t-shirt, and he lit up when he learned that I spent 20 years as part of a mountain rescue unit. He was of course intrigued to know that I co-founded a high school myself, but he really became excited when he learned that I had come into that work out of decades in the field of outdoor and experiential education. He too worked in this field, and in fact started an outdoor adventure camp wherein Katya’s kids participated in events like rock climbing and mountaineering. It doesn’t hurt that he has an impish nature and a twinkle in his eye!

We got a tour of the facility while hearing stories of Serhii’s efforts to develop the programs that will bring the fruition of his vision. Yet there is no clear developmental path. In the early stages of this process, after acquiring two adjacent retired school buildings and beginning to renovate them, the full-scale invasion began. As immediate response to the invasion became a top national priority for all Ukrainians, Serhii and his folk high school project pivoted in response.

This is a good point at which to note that the Russian invasion, the Russian war, in the eyes of Ukrainians, began in 2014 with the illegal seizure of Crimea. That this invasion was not more aggressively addressed by the US is why many in Ukraine see Obama as a weak and ineffectual leader. Viewing the war through a larger lens, it started in 2014 and February 2022 is considered the start of the full-scale invasion.

In a corner of a classroom I spied this plaque of the Ukrainian national symbol, the trident, made from bullet casings, along with an emergency medical symbol highlighting the medical training the Folk High School provides. A fascinating contrast between tools of harm and tools of help!

Serhii’s pivot led him to launch an emergency medical training program with the support of a Swedish foundation and an initial batch of Swedish trainers. They have by now run hundreds of people through this program, developing along the way a group of their own trained faculty so that they were less reliant upon foreign support. Innumerable Ukrainian medics, including those in fire departments and other emergency services as well as military personnel, have been trained through this Folk High School.

Serhii Chumachenko and I both have roots in adventure education, an enacted vision of starting a school, and a certain playful nature.

Numerous other initiatives are in process at the nascent Vovchok Folk High School. There are events happening for children at the school building that was the village public school before the government consolidated schools in 2016. They have initiated teacher training workshops in the Bildung movement and have run several rounds of these. More centrally, the school aims to serve the adults of the village. Serhii described this village as having 500 people, many of whom even before the war were losing hope amid growing economic and metal health pressures. The school gathers villagers to dialog about the future, along the way rekindling a sense of hope.

The curriculum of the teacher workshops has five components, Serhii explained. They are: • “Northern philosophy,” which speaks to the civic thinking behind the Bildung movement itself. • Introducing outdoor leadership skills. • Cultivating the village as the center of society. • Entrepreneurship to foster self-determination and initiative. • Celebrating local food and culture. It’s a package designed to both foster individual growth and develop a healthy, generative, decentralized community. There is an open-endedness to it that I find inspiring, since it is rooted in a school-as-community-center model rather than school-as-isolated-institution model. Unsurprisingly, our time with Serhii reflected each of these tenets in some way.

During our discussion, we walked through the two buildings that Sergiy and his team have been renovating. One, a log cabin built initially in 1888, is now a highly functional, rewired and replumbed center with two classrooms, bathrooms, and a kitchen. The larger building was first built in 1914 and now has new bathrooms, showers, and kitchen, along with a fourteen-bunk dormitory upstairs, consisting of two bunkrooms of five and two rooms for leaders. The downstairs is still very much a construction zone, but Serhii proudly pointed to a wall in the gym where he hopes to install a climbing wall.

This lineup of traffic crossing a floating bridge is just one of many inconveniences that Kyiv residents face as they live under ongoing threat from Russian attack.

We returned to the log cabin to enjoy delicious homemade poppy seed rolls and birch tea and continue talking — manifesting the food and culture element of Folk School philosophy — but our time was nearly up. We picked up a few locally made beeswax candles (produced by a war widow in the village) for souvenirs and received gifts of coffee cups celebrating the Folk High School. Once again, our parting was warm, and I feel certain that Serhii and I will continue to be in contact.

On our trip back to the city I conversed with Jaroslav, the graphic designer and friend of Katya’s who had been working with Serhii at the Vovchok Folk High School. Jaroslav is the founder of Kyiv Design Week and several other design initiatives, including several annual multi-arts festivals. We spoke about arts and democracy, and the need not just in the US but everywhere to redefine democracy. Democracy 2.0 was his term, though considering the history of the Iroquois Confederacy I suspect the correct number is higher. We explored the need for participatory governance rather than representative governance. I was struck, again, with a sense of surreality: Driving through Kyiv traffic, conversing in depth about the future of democracy! At one point we crossed over a floating bridge that was set up to deter any Russian tanks that might get that far: Another reminder that the war is ever-present yet not overemphasized part of Ukrainians’ daily patterns.

The gardens at Katya’s family home are immaculate and extensive. Gardening seems to be a global language of sorts.

Before heading home we stopped at Katya’s parents’ suburban home, partly to pick up their son Petras who was there for the weekend, and partly to meet Katya’s folks. They were very gracious and kind people, like nearly everyone I met in Ukraine.

Four generations of the Yasko family pose in front of their home.

Sitting on the banks of the Dnipro, their gated estate has lush gardens, fruit trees of many sorts, neat lawns and paths, and a view out over the river. This place was a gift to Katya’s mom from her dad in honor of International Women’s Day, and he built it himself. In touring the grounds with Katya’s mom, she shared this story. And then, tears in her eyes, she related how Russian attack drones fly low over the river most nights attempting avoid radar on their way toward targets in Kyiv. The drones have become a nonstop menace to her beloved sanctuary. “I don’t know when it will end,” she said.

The remainder of the evening was short since it had been such a long day. We skipped dinner, essentially, while Katya engaged in a debate on Facebook and I conversed with Anya, Katya’s daughter. We discussed theatre, complexity, relationships, and maturation. It was a very nice chat unto itself, and highly remarkable in that this is a 17-year-old woman with the clarity and presence to readily and openly engage in such topics. Needless to say, I was impressed. My last memory before falling asleep was reading a NYT article about how Ukrainian volunteers are organizing to waylay drones on their way to attack Kyiv.

It was only a short time before the drone drama in the skies over Kyiv awakened me, an experience described in the first essay in this series.