Sometimes, out of the vast swamp of issues that vie for our attention, something rises up and calls us to immediate action. A travesty taking place right now in the Wet’suwet’en First Nation of northern BC represents such an urgent call to act.

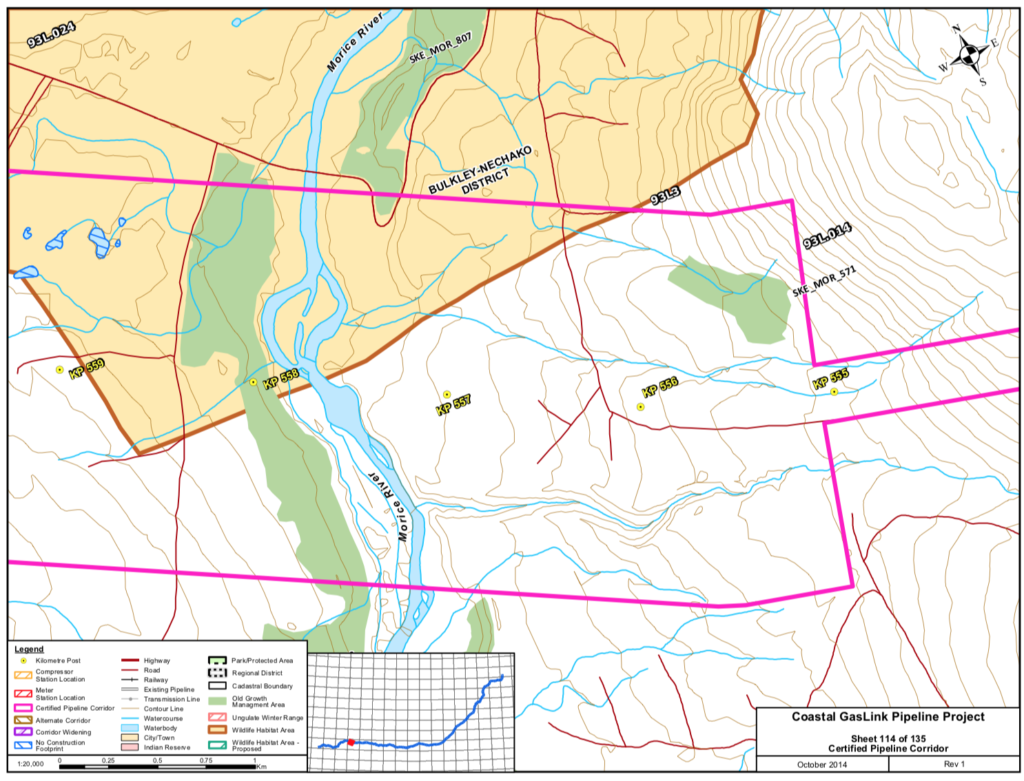

As I write, Coastal GasLink pipeline crews are tearing down a wide swath of old growth forest to establish a right-of-way for a fracked-gas pipeline.

And this “right-of-way” in fact has no legitimate right to be there: It is being built in Indigenous sovereign territory over the strenuous objections of the Wet’suwet’en people. The principle of free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples regarding use of their land is being criminally disregarded.

I recently returned from Wet’suwet’en territory where this travesty is unfolding. While there, I had a chance to hike into the wild lands that the Unist’ot’en – one of the clans of the Wet’suwet’en – call home. It was still winter there, so we traveled on snowshoes through rolling woodlands and across frozen lakes. Being in that place, it is easy to see why they call this the Yintah, or sacred territory: It is beyond beautiful in its quiet repose.

The purpose of our hike was to identify culturally modified trees and record their locations. This work documents historical Indigenous use of this territory. The fact that Coastal GasLink is trying to deny and discredit Indigenous land rights would be simply pathetic – if they hadn’t gotten a temporary court injunction last December allowing them to act as if such rights don’t exist. This speaks to a failure of the Canadian legal system; more on that in a moment.

As we traipsed through the lovely forest, we were busy, since there were plenty of modified trees to document. Yet after ten or twelve kilometers of hiking, we came across a flurry of orange flagging ribbons. This was the surveyed pipeline route. Suddenly the beauty of the woods was thrust into shadow, its isolation rejected, its future threatened. Now burdened by visual as well as abstract awareness of the threat, we followed the line to where the chain saws and bulldozers were at work.

Here was destruction of a type and scale I’d rarely encountered. A huge swath of woods, roughly two hundred meters wide, had been mowed down. Bulldozers had crushed creekbeds beneath their bulk. I’ve seen many clearcuts and built many wooden structures, so logging is not foreign to me. But here, the trees had not been harvested but instead laid out parallel for heavy equipment to cross wetlands. It was a horrifying view. And it came in sharp contrast to a day of hiking through peace and beauty.

Thus my call to action. It is outrageous that Indigenous rights are being trampled under a thin premise of legality. It is dismaying that in this era when the climate crisis has made fossil fuel developments untenable, such projects are still taking place. And the image of devastation severe enough to make a clear cut look good turned my stomach.

The impacts on wildlife, soil, and the climate are not.

We don’t have to accept this. I consider this struggle the “Standing Rock of 2019.” Yet the Wet’suwet’en First Nation has a much stronger legal position in this fight than the Sioux did at Standing Rock. With enough public attention bearing on the Coastal GasLink pipeline, it will be stopped. And it must.

The fossil fuel tide is turning. In this past week, the Waorani Tribe of the Ecuadorian Amazon won a court ruling that stopped oil and gas leasing on their sovereign lands. And in New York, the Williams fracked-gas pipeline was just dealt a setback when the New York Department of Environmental Conservation ruled unacceptable its impacts on water quality. Coastal GasLink can be stopped too – given concerted effort.

This is a critical time. The temporary injunction “authorizing” the current destruction is coming up for reconsideration in a few weeks. Will it be rescinded, or made permanent?

We are not powerless. Here are some examples of possible actions. There are enough options that every concerned person can do something.

• Become more informed. Learn more about the Unist’ot’en position and pay attention to learn the outcome of the new court hearing.

• Donate (or help to raise) money. Legal fees to sustain the fight against Coastal GasLink’s unjust injunctions and regular pledge funds are needed.

• Travel to the Unist’ot’en Village yourself. Coming to volunteer at the site is the best way to understand the impacts of the pipeline project.

• Write letters to the editor to raise awareness about this issue. Contact your local media and help others learn of the “Standing Rock of 2019.”

• Write to Canadian officials to urge them to act. Some contact numbers are listed here.

• Contact banks – especially Chase – to urge divestment from Coastal GasLink. Without massive funding, pipelines can’t be built. Anyone can visit a local Chase branch and talk with the manager.

• Prepare to join a rally in Victoria or Vancouver when the hearing takes place in June; you’ll have to be watching to know what is going on.

Our focused and sustained action will make the difference.

One day in the Yintah, I was stopped by the RCMP on a gravel road forty miles from the nearest town. One might wonder why the RCMP would even appear on so remote a road. The answer: they are acting as a de facto military force, enabling unauthorized pipeline crews to invade and damage the Yintah. Since the court injunction was issued last December on behalf of Coastal GasLink, the RCMP have dealt violently with anyone in the way of pipeline crews.

Standing in the dusty road, one of the officers checked the registration on my vehicle while the other stood stiffly by, presumably watching to be sure I wouldn’t commit any crimes. I had to tell him that, despite my historical respect for the RCMP, I was greatly disappointed in him. I explained that the RCMP was making a mistake in supporting yet another invasion of Indigenous territory. He hastened to say that he wasn’t there to argue, that he was just doing his job and enforcing the law. I didn’t buy it.

“The problem with that position, sir, is that there are different sets of laws. Some are in conflict with others. So you have to decide which laws to enforce. I believe you are on the wrong side of morality, the wrong side of history, and indeed, your presence here is enforcing the wrong laws.”

He shuffled uncomfortably, but repeated that he wasn’t there to argue. I told him I wasn’t there to argue either; I just wanted him to reconsider the position he was taking. I don’t have much confidence that he did.

This was not my first visit to the Yintah. For several years, I’ve been traveling the 800 miles north from Bellingham to the wild east slope of the Coast Range that is the home of the Unist’ot’en. I have helped create a Healing Centre and the settlement that has grown up around it. I’ve had the privilege of meeting Unist’ot’en elders and hearing stories about the ancestors. I’ve seen coyote, moose, bear, beaver, and pine martens that also call this place home. I have myself experienced some of the healing properties of the Yintah.

This Centre is a unique facility. Here, Indigenous people who suffer from any number of maladies associated with decades of mistreatment can come put their lives back in order. The Centre incorporates traditional therapies with an Indigenous approach of bringing people back into contact with their sacred territory. They spend time in the wilderness, they learn to trap and hunt and fish, and they talk not just with therapists but with elders who help them find their way back onto a good path.

In my past visits, the Healing Centre was quiet. The river called the Wedzin Kwa rushes past. Occasionally a logging or tree planting operation was active nearby, so work crews and trucks would pass by from time to time.

But the Yintah is no longer quiet. It is under siege. Dozens of trucks rush past every day, carrying surveyors, loggers, heavy equipment operators, laborers, security and communications personnel. The destruction they are bringing into the Yintah echoes generations of past injustices against Indigenous peoples. It is wholly unaccepable.

Will you take time to act?

And we wonder why the Indigenous Attorney General of Canada was summarily let go, a few months ago? Money and greed seem to be the common denominator of victimizing Indigenous people and their home lands.

Is justice in BC, blind or just blinded by the limited appeal of a few thousand construction jobs? Where is the S.P.I.C.E.S of Canada?

Native culture & land are far too precious and rare to miss use for the gain of a few. Sustained, prolonged truths will need to be held in the Light for not only the Wet’suwet’en nation but the Unist’ot’en clan. The genocide of the people is morphed into the final destruction of their sacred land. There is hope to stop this before the environmental and cultural aggression becomes the latest weapon used against a people who cling to their way of life. May my Creator and all of my ancestors and myself help those who are the stewards of magnificent wonders called the Yintah.

Thanks very much, J. Lee, for your thoughtful comments. For any readers who may be unfamiliar with the reference to S.P.I.C.E.S., this is an acronym representing the Quaker principles of Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality, and Stewardship. Although many of our allies have no affiliation with the Quaker faith, they often share a commitment to these important values.

It’s such an interesting issue. Although it is still difficult for me to understand. This is in the USA or in Canada?

What is RCMP?

what I know it is such a beautiful landscape and what a pity that this territory of the indigenous people is destructed for a pipeline project. Can’t they consider or analyze the sustainability of the natural resource and the wild life of the land? Can’t they find another route except Yintah?

This essay is about a Canadian pipeline passing through the Indigenous, Wet’suwet’en territory known as the Yintah. The RCMP — apologies for the assumption that this was a familiar term — is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. As described in the main post, the RCMP are unfortunately on the wrong side of the law in this circumstance: Protecting outside moneyed interests over those of citizens.

Your second query, Intan, is a pointed one: Why, indeed, CAN’T Coastal GasLink recognize the fragility and value of the wild land and its rightful, Indigenous stewards? I believe they are blinded by money. And I think they are desperate to try and get their filthy petrochemicals to market before the market collapses completely, which will cost a lot of rich people a lot of money. We have a ways to go before the rights of people and Nature are held as equal to those of corporate interests.

Thanks so much for your comments and concerns!