In Ubud, they will rent a scooter to almost anyone!

The town of Ubud is like ice cream: It is a rich and wonderful place, but take in too much of it, and the pleasure disappears.

On Valentine’s Day, I arose early and cruised Ubud seeking flowers and a latte for my sweetheart. This marked a new phase in my use of Bahasa Indonesia: “Di mana toko bunga, mahon?” I built this phrase mostly from known words and managed to make myself understood with the query ‘Where is a flower shop, please?’ Similarly, “Saya mow bungas untuk saya wanita” means ‘I want flowers for my woman.’ Of course the replies were rapid and unintelligible! It took some wandering, but my efforts allowed Lisa to awaken to flowers and coffee.

Fragrant, brilliant, abundant — the flowers of Indonesia are an everyday sensory delight!

We’d had our fill of Ubud, so we set out on our scooter to see the northern and eastern portions of the island. It’s worth noting that despite having a robust population of 4.25 million and a reputation as a cultural hotspot, Bali is quite small. The entire island stretches just 90 miles in its longest dimension. Thus, we left southern Bali after breakfast, and despite meandering along winding backroads, we reached the rim of the volcano by mid-day.

Rice fields can work on incredibly steep hillsides — with enough manual labor.

Mileage aside, we gained around 1500 meters of elevation in a lateral span under 30 kilometers. This made the roads and hillsides along our route quite steep. We saw monkeys being fed by tourists at viewpoints along the road, improbably steep rice paddies marching up hills like green stairs, fruit stands offering succulent mangosteens and tangerines, and eventually the steep rim of an ancient caldera. There we looked out across a vast crater encircling a lake and the young cone of Gunung Batur. The basin was ringed by villages, farms, gravel mines and lava flows, as well as the waters of the lake Danau Batur.

Gunung Batur is an active young volcano, perched in the caldera of its fallen ancestor.

On an impulse, we descended from the crest into the basin to trace the road around the volcano inside the yawning caldera. Some of the scenes around the expanses of lava were more ghostly than beautiful, with a certain lovely ominousness: This is a living volcano that in our lifetimes has erupted multiple times. Discovering a shortcut, we took an incredibly steep road back up to the rim.

And then we dropped northward to the coast. If ascending the volcano was steep, heading down was more so: this time, our 1500 meter drop to sea level spanned just ten horizontal kilometers. This made for a very long and winding road that a bicyclist could likely traverse without pedaling! We reached the shore around dusk and checked into a nice resort to enjoy a couple of days of leisure. In three weeks of travel, we realized we’d not yet stayed put once without filling our days with activity. So we savored a bit of repose.

We nicknamed our two-headed raingear the “divorce poncho” — it kept us (somewhat) dry only when we coordinated our movements.

Resuming our travels, we skirted eastward along Bali’s north coast. The route offered many beautiful views of jungles, rivers, villages, and the Bali Sea to the north. Curving southward around the flank of Gunung Agung, we stopped in the seaside surfer town of Amed for lunch. There, we sat out a rain squall and greatly enjoyed a meal of pepes ikan, a Balinese specialty of spicy fish cooked in a banana leaf that has become one of our favorites.

The foods of Indonesia reflect both its ecosystems and cultures. The ubiquitous rice fields through which we wandered are reflected in nasi goreng, or fried rice, that can be found on the menu of every warung. We ate nasi goreng nearly every day, never tiring of it. The spin that each chef puts on the recipe keeps it from being monotonous. And it’s healthy, economical, and filling, coming with egg, seafood, or tofu, or chicken. We found it as satisfying for breakfast as it was for dinner.

Fruit! Mangosteens, tangerines, dragonfruit, bananas, rambutans, etc. Yum!

The tropical setting of Indonesia is extravagant in fruit production. Bananas, tangerines, papayas, mangoes, and pineapples are not only abundant here, but they demonstrate a variety and succulency unknown in temperate climates. The fruits that don’t reach North America delighted us the most: Mangosteen – buttery smooth, sweet and rich in a purple skin; Silak – coarse scaly skin in a garlic-like shape of firm pear-like flesh; Rambutan – strip the crazy, fringed red orb to reveal a juicy sweet eyeball of fruit; Purple Dragonfruit – a luscious soft flesh nearly erotic with magenta and sweetness; Jackfruit — yellow pods from a large gourd with a sweet buttery flavor. And then there’s the misunderstood Durian, unpleasantly pungent after oxidizing, but mild and sweet when extremely fresh. (One hotel where we stayed had a strict no-durian-on-the-grounds policy!) One could spend a lifetime eating, painting, savoring, and describing the wonderful diversity of island fruits! We also enjoyed fresh-pressed, amazing fruit juices every day.

Silak, or snakefruit, hides its firm and sweet flesh inside a rough scaly skin.

Durian has an earthy, almost hormonal scent and flavor — to enjoy, eat it when it’s VERY fresh.

The purple dragonfruit is sweet, rich, juicy, and sensuously gorgeous.

Fried tempeh is common to Indonesian cuisine. I’d always thought of tempeh as having Japanese or Chinese origins, like tofu. As it happens, tempeh was developed on Java, making it a more-or-less indigenous food product. More-or-less, because tempeh is a by-product of the manufacture of tofu, a process brought to Indonesia by Chinese traders. Tempeh is traditionally fried and is great as a protein side dish or mixed into stews or curries.

Curry is another Indonesian food that reflects the cultural geneaology of this place. The South Asian traders and merchants that brought curry here also brought Hinduism and Islam. (Buddhism, too, though this faith did not persist to the same degree.) Like the food itself, these faiths have evolved a local flavor that sets them apart.

Pantai Aas is a picturesque spot near Bali’s easternmost point.

Drenched roads get a bit iffy when potholes lie submerged and hidden.

After lunch we skirted the eastern point of Bali in the rain, following a tiny coastal road. Many of the vistas were enhanced by the swirling clouds, but crossing flooded roads on a scooter (where deep potholes are common) was unnerving at times. And a scooter suited to errands in the city gets tiring to the posterior after hours of travel. So we turned into a park-like area for a break, and discovered that we’d arrived at the water palace of Taman Ujung.

Taman Ujung is the most grandiose display of Balinese architecture and landscaping we visited.

This sprawling enclave, over 100 years old, is more a puri (castle) than pura (temple), though its location at the junction of mountains, hills and the sea, is deemed holy. Of its three pools, the original one was built as a place to purify/punish practitioners of Balinese black magic. One wonders, in looking at the magnificent beauty of Taman Ujung’s structures, pools, and gardens, what sorts of good and evil played out here. The architecture reflects Dutch, Balinese, and Chinese influences. The pastoral scene is popular for weddings and bridal photos, but statues of grimacing demons hint at the darker stories buried in the place’s history.

Another stop on our east Bali loop was the tribal Aga village of Tenganan. Here, amidst the inescapable trappings of tourism, one can envision animistic Aboriginal people honoring the spirits of the mountains, trees, and rocks. We enjoyed talking with local artisans, the descendants of Bali’s original people. It was not hard, seeing the ornate Hindu figure of Ganesh etched into bamboo, to glimpse the mixing of Indigenous Balinese with the Hindu immigrants that began nearly two millennia ago.

This ornate mosque seemed out of place in a tiny village of a few small houses — note the dirt road.

It is wonderful when the mixing of faiths does not precipitate conflict, as we see far too often. Our experiences of Islam — mostly on Borneo, Flores, and islands other than Bali — were limited to seeing men wearing thaub and kufi (tunic and hat) and women wearing hijab, as well as hearing calls to prayer broadcast from nearby mosques. These broadcasts were compulsory to anyone near a mosque. They came out sounding like nasal chants, sweeping through whatever area as the mosque’s loudspeakers could reach, at dawn, noon, midafternoon, sunset, and nighttime. In one town, there seemed to be a competition between two mosques a block apart to see whose chants could be more widely heard.

Young girls wearing headscarves are a common sight in the Muslim areas of Indonesia.

While we admired the beautiful clothing of the Muslims, and were impressed with the devotion of the faithful streaming in and out of prayer, I cannot say that the calls to prayer were pleasant to the ear. It seems good, though, that Islam in Indonesia seems to be a more moderate sort than places in the Middle East where Sharia law prevails. (Northern Sumatra, which we didn’t get to on this trip, is an exception.) In truth, though, I am not much familiar with Islam.

Temples and shrines seem to be nearly everywhere in Bali.

While Indonesia has the most Muslims of any country on earth, Bali’s unique history has made it predominantly Hindu. And Bali is where we spent the greatest amount of our time in Indonesia. (In an earlier post I described the opportunity Lisa and I had to attend a Hindu ceremony.) I’m no religious scholar. Yet the blending of Bali’s original collectivist, animistic faith with Hinduism seems to have produced a rich result. The most amazing thing about Hinduism in Bali is that it is at once both inescapable and unobtrusive. We never felt anything but kindness and openness from Hindus. Yet in even the tiniest villages, there’s at least one temple, and temples are found in hotels, parks, government complexes, quiet roadsides, lakes, shorelines, you-name-it. We even visited one temple built in a cave.

At opening time, a young woman heads out to distribute offering baskets around her shop.

But why limit your faith to visiting temples? Every Hindu home and business has some kind of shrine, offering, or blessing place. It is common to see offering baskets filled with brilliantly colored flowers, incense, a few grains of rice, and sometimes a small snack or cigarette, placed daily on the sidewalk in front of homes, stores, and offices. This – along with the building of temples – is so widespread that I came to see it doubling as a job-creation program. Often a selection of baskets and colorful arrays of flowers is displayed in local markets.

Even bathrooms often be the site for floral offering baskets.

In Bali, I passed the 24-hour mark, the point where my meditation time in 2018 equaled a full day. This reflects a half hour per day of sitting in silence, times 48 days in the year. I think of this as mindfulness exercise, since no religious dogma accompanies my sitting. But ‘meditation’ has half the syllables as ‘sitting mindfulness exercise.’ Even simpler: ‘breathing.’

Flowers bring spectacular color to every garden!

I don’t talk about this part of my life much. But in Bali, a link emerged between my outer experience and my inner experience. Sitting on a rooftop terrace in one village, I reached the 30 minute mark feeling that I’d just begun. I’d somehow found a sense of emptiness that made time disappear. Though I don’t have words for this, I believe it emerged from the spiritual presence of a place where there are multiple shrines every block and offering baskets are everywhere. It is as if a certain reverence lies just beneath the surface of Bali, affecting those who are open to it.

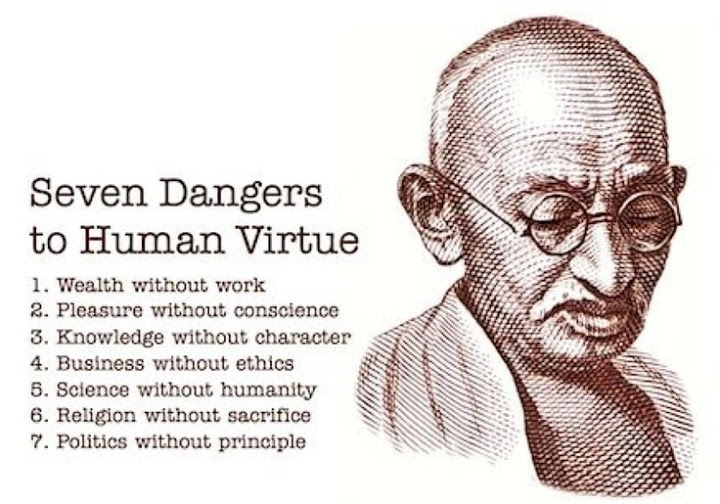

One of my breathing sessions took place at the Gedong Ghandi Ashram near Candidasa. We found this seaside yoga retreat because it was on our National Geographic map, and since Mahatma Gandhi is one of my personal heroes, it sparked my curiosity. I enjoyed sitting and breathing in a vacant yoga pavilion near the beach, the poster I’d just seen featuring Ghandi’s list of seven “dangers to human virtue” fresh in my mind:

If there is a solution to the challenge of building peace between faiths, I think Gandhi can help us find it. His simple words, like a small basket of flowers, convey purpose, beauty, and hope. In them, we may find the wisdom to lead us toward a peaceable world.

Rice, flowers, and incense offerings are left on the cobbles in front of a home to mark the holiness of daily life.

The name of the fruit it “salak” not “silak”, daniel 😀 it is also translated into English as snakefruit

And we only call it “tempe” not “tempeh” with “h”

Really enjoyed this and the previous one. Well crafted and educational. We are thinking of heading to Indonesia next year for our 30th Anniversary and this is helpful. Your essence as educator really comes through in your travel journaling.