Two trendlines are coming together and becoming part of the fabric of our lives.

One trend, as reflected in a recent Time magazine cover story, is the rise of such mental illnesses as anxiety and depression. In the world of adolescents, fully 25% have had a diagnosed anxiety disorder, and about half that many have had a depressive episode in the past year. Such conditions often emerge in the teenage years, as young people face the challenges of body change, establishing an identity independent of their parents, building healthy peer relationships, and finding a sense of meaning to carry them into adulthood. But adults are vulnerable, too. Rates of adult depression have roughly doubled in the last generation.

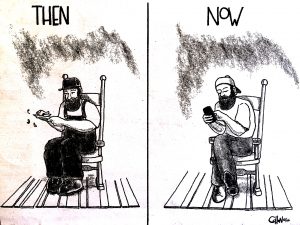

The other trend has to do with our reduced level of connection with the natural world. Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, coined the term Nature Deficit Disorder to reflect the increasing isolation beween children and nature. This is not, to Louv, a medical diagnosis as much as a descriptor meant to call attention to our distant and dysfunctional relationship with wild places. He identified one factor as the paranoia that makes parents reflexively consider natural settings risky and want to protect kids by keeping them indoors. There are also fewer natural places accessible to our urbanized population. Further, schools, already under financial pressure, are increasingly expected to prepare kids for tests, which means fewer field trips. And of course there is the ubiquity and magnetism of electronic distractions.

These intersecting trends are certainly related, though it will be a while before their exact relationship is documented. What we can do is to look around at how our lives, families, and schools are affected. Awareness can then guide plans of action to enrich our lives, even if we don’t experience symptoms of depression and don’t lack time spent with nature.

I like to envision a continuum that has on one end, a completely developed or human impacted environment – like a downtown parking lot – and on the other, a completely unimpacted environment, such as a remote forested hillside. Where on that continuum do we live? Do we regularly venture into places where nature is the predominant force, as opposed to pavement, the sound of engines, and artificial light?

I like to envision a continuum that has on one end, a completely developed or human impacted environment – like a downtown parking lot – and on the other, a completely unimpacted environment, such as a remote forested hillside. Where on that continuum do we live? Do we regularly venture into places where nature is the predominant force, as opposed to pavement, the sound of engines, and artificial light?

During my teenage years near Chicago I felt (but lacked a language for) this continuum. I lived on a wooded lot, thanks to my father’s hobby of planting trees, but a major highway near my house was always audible. A car dealership’s outdoor intercom barked out announcements, and jets taking off from O’Hare were a constant. So when I got the chance, I would drag my friends off to a “forest preserve” an hour’s drive away, where we could lose ourselves in what seemed like endless hills, swamps, meadows, valleys and winding creeks. Did the days I spend in those places help me keep my sanity? I think so.

More recently I was working on an urban ecology project and found myself in a spot near downtown Seattle. In the core of the city I found a wildness I would never have expected. Directly beneath I-5, where cement columns rose to support the constant traffic above, lay a woodland of sorts, laced with trails, thick brush, scattered campsites and an untamed atmosphere. The towering concrete shafts felt very like trees, in some places no buildings were visible, and the rushing of the vehicles formed a white noise not unlike that of a waterfall. Wilderness it wasn’t. But there was a soothing quality that struck me with awe.

When I built a school, I worked with my co-founders to regularly bring our students into frequent, in-depth contact with nature and the outside world. Over the years of its existence, that school brought many students into a kind of contact with their environment that was both educative and restorative to them. It was not a panacea, but it created for many kids a valuable touchstone in an often-chaotic life.

The wild is accessible. It is our first, largest, and most important classroom. We just need to make a priority of being in it. Leave the device at home, and the time you spend in contact with nature will all but compel you to put the complexities and struggles of modern living into a healthy perspective.

The wild is accessible. It is our first, largest, and most important classroom. We just need to make a priority of being in it. Leave the device at home, and the time you spend in contact with nature will all but compel you to put the complexities and struggles of modern living into a healthy perspective.

If one steps out on a starry night and observes one’s inner state, one asks if one could hate or be overwhelmed by envy or resentment. Is it not true that no man or woman has ever committed a crime while in a state of wonder? — Jacob Needleman

Parenting Tip: Get your teenager to go for a walk with you in the evening. Leave your devices (both of you!) at home. In the darkness, there will be no witnesses or eavesdroppers, and the fact that facial expressions cannot easily be seen may help create a sense of safety for expressing vulnerable feelings or ideas. The fresh air and weather may draw you together. Allow yourself to tell some stories or express some vulnerabilities, and see what happens.