Did you ever wonder why we have just one word for winter, spring, and summer, but, when it comes to this time of year, we can say either ‘fall’ or ‘autumn?’watch full movie The Exception 2017 online

I was chided once by a British friend for using the word ‘fall.’ To him it seemed crudely American to trade the elegance of the word ‘autumn’ for the vernacular ‘fall.’ At the time, neither of us knew that ‘fall’ was once popular in the UK, where it started out as the rather more prosaic ‘fall of the leaf,’ which has quite a pleasant pastoral ring, yes?

‘Autumn,’ as it turns out, is a word with its source in Latin – so my friend’s high-mindedness about vocabulary was more than a little misplaced. But isn’t it fun to consider the varieties and uses of words?

An essay I read recently by the linguist John McWhorter dives into and celebrates the motley menagerie that is the English language. McWhorter shares numerous insights into the oddities of our language. For example, he asserts (and who am I to question an actual linguist?) that English is so unique in its spelling conventions that spelling bees – an elementary school highlight for me – are held only in this language. Turns out there is no point in a spelling bee where spelling is consistently linked with pronunciation!

An essay I read recently by the linguist John McWhorter dives into and celebrates the motley menagerie that is the English language. McWhorter shares numerous insights into the oddities of our language. For example, he asserts (and who am I to question an actual linguist?) that English is so unique in its spelling conventions that spelling bees – an elementary school highlight for me – are held only in this language. Turns out there is no point in a spelling bee where spelling is consistently linked with pronunciation!

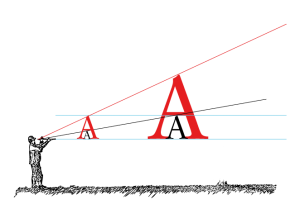

Another bit of playful intrigue in that essay is a comparison of synonyms. Take ‘help,’ ‘aid,’ and ‘assist’ – it isn’t too hard to imagine going up a scale from basic to pretentious in that list. Imagine coming up to someone who just dropped his groceries in a store and saying “May I assist you?” You’d as likely get a dirty look as a word of thanks! In fact, as one with a robust vocabulary, I have been accused of egotism by using certain words, as if I was trying to pull rank or something. Hardly! It’s simply the fact that, possessed of a large box of toys that are words, I simply want to play!

A similar triad from Mr. McWhorter’s essay is ‘kingly,’ ‘royal,’ and ‘regal.’ Again there is a gradient of apparent formality, which it turns out is rooted in the words’ source language. Like the set of three synonyms above, the first is English in origin, the second, French, and the third, Latin. This delineation is associated with the status of those languages (and their speakers) in historical England.

Did you ever wonder why, when slaughtered and prepared, a cow becomes beef, a pig, pork, and a deer, venison? McWhorter again guides our gaze to history, where we have William the Conqueror to thank for these savory morsels of vocabulary. When William and his French allies subjugated England in the Norman conquest, it was common for English speakers to kill and prepare the animals, while it was French speakers dining on the roasted meat. As a result, beef, pork, and venison trace their origins to French.

Perhaps there is truth to the idea that larger vocabularies are a tool to impress. But there is nonetheless great joy to be had in a romance with the myriad textures and colors of words.

I’ll close this piece with a story. (Or perhaps you’d call it an anecdote!) I had a half dozen teenagers in my car on the way to a trailhead to start a hiking trip. We were talking about driving and the hazards these kids would face as they earned their driving priveleges, and I mentioned that changing music settings had been named as one of the leading causes of accidents with teen drivers. This triggered a robust discussion, in which a word arose – I wish I could recall which word – that nobody knew the exact meaning of. So I pulled my dog-eared paperback car dictionary out from under the driver’s seat and handed it to the youth next to me.

“Look it up!” I said, as the passengers all burst into amazement at the fact that I carry a dictionary in my car.

The guy to whom I handed the dictionary gave me a look, and declared wryly, “You know, the leading cause of accidents by school directors is reading dictionaries while driving…”

The guy to whom I handed the dictionary gave me a look, and declared wryly, “You know, the leading cause of accidents by school directors is reading dictionaries while driving…”

If you love words and the stories they tell, take a look at McWhorter’s fascinating essay here.